Zemindar docked in unknown harbour. Photo courtesy of State Library SA Approximately 1895

Zemindar docked in unknown harbour. Photo courtesy of State Library SA Approximately 1895

Matilda was the eldest daughter of Isaac Wallis, a mason, and Mary Selina Hunt of Back Lane, Highworth (Wiltshire). She had three younger siblings; Elizabeth, George and Charles. At age 8 , George was listed as living with his grandparents in Lower Street, Highworth. Matilda travelled to Australia on the Zemindar ship arriving in Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) on 23/8/1957.

'In the early 1800s, the colonial population was predominantly male, made up of convicts, soldiers, and agricultural workers. Recognising the need for more single women in Australia, the Emigration Commission began advertising for women in search of employment, marriage, or a new life. Initially, ships were chartered for the exclusive use of single women but later the Emigration Commission provided single women with assisted passage on standard government emigrant ships. Eligibility criteria varied, but the Commission usually only accepted single women aged between 18 and 35 who could prove their physical and moral soundness. '

https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/shipboard-19th-century-emigrant-experience/female-emigration

'In the early 1800s, the colonial population was predominantly male, made up of convicts, soldiers, and agricultural workers. Recognising the need for more single women in Australia, the Emigration Commission began advertising for women in search of employment, marriage, or a new life. Initially, ships were chartered for the exclusive use of single women but later the Emigration Commission provided single women with assisted passage on standard government emigrant ships. Eligibility criteria varied, but the Commission usually only accepted single women aged between 18 and 35 who could prove their physical and moral soundness. '

https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/shipboard-19th-century-emigrant-experience/female-emigration

Matilda 's journey is an interesting story. The Dunbar was due to arrive on the same day as the Zemindar but was dashed against the cliffs at the Gap during gale force winds and rain. 121 of the 122 souls aboard were killed. A lone seaman survived. Matilda is likely to have witnessed the debris of the Dunbar as her ship sailed into the harbour the next day. Her son David William mentions this in his reminiscences (below). I have written a factional story based on Matilda's voyage to Australia including reference to the Dunbar. It is a longish story (5000 words) and was accepted for the anthology Colonial Women (published by the Society of Genealogists in 2022). I hope you enjoy reading it.

In 1839 Matilda married David English Corney in Glen Innes. She was working there as a servant and David was droving at that time. They moved to Tenterfield where David set up coach building before working in the building trade. See DAVID ENGLISH CORNEY for more information about his life. The family settled in Bulwer St, Tenterfield. They had nine children together, seven of whom survived into adult hood. Charles Henry (1861-1968), David William Hunt (1864-1865), Albert (1865-1920), David William (1868-1956)*see article below , Mary Elizabeth (1871-1942), Annie Matilda (1873-1910), George Thomas (1875-1961), John Michael,(Jack)(1877-1931), Clara (1878-1878) and Lillian May (1878-1938).

In 1898 Mary Elizabeth married Robert Henry Morris (my great grandparents). See MARY ELIZABETH CORNEY & ROBERT HENRY MORRIS for more information about them. In February 1910 Annie Elizabeth (Mary's sister) married James Herbert Morris (Robert's brother). Unfortunately the marriage was short lived as Annie died in November of that year after a 'short illness.' The remaining daughter Lillian May devoted herself to caring for her parents and she never married. Matilda died in 1931, ten years after her husband David.

TRANSCRIBED FROM THE TENTERFIELD STAR NEWSPAPER,: Thursday, October 1, 1953

MEMORIES OF EARLY TENTERFIELD, DAVID WILLIAM CORNEY

In 1839 Matilda married David English Corney in Glen Innes. She was working there as a servant and David was droving at that time. They moved to Tenterfield where David set up coach building before working in the building trade. See DAVID ENGLISH CORNEY for more information about his life. The family settled in Bulwer St, Tenterfield. They had nine children together, seven of whom survived into adult hood. Charles Henry (1861-1968), David William Hunt (1864-1865), Albert (1865-1920), David William (1868-1956)*see article below , Mary Elizabeth (1871-1942), Annie Matilda (1873-1910), George Thomas (1875-1961), John Michael,(Jack)(1877-1931), Clara (1878-1878) and Lillian May (1878-1938).

In 1898 Mary Elizabeth married Robert Henry Morris (my great grandparents). See MARY ELIZABETH CORNEY & ROBERT HENRY MORRIS for more information about them. In February 1910 Annie Elizabeth (Mary's sister) married James Herbert Morris (Robert's brother). Unfortunately the marriage was short lived as Annie died in November of that year after a 'short illness.' The remaining daughter Lillian May devoted herself to caring for her parents and she never married. Matilda died in 1931, ten years after her husband David.

TRANSCRIBED FROM THE TENTERFIELD STAR NEWSPAPER,: Thursday, October 1, 1953

MEMORIES OF EARLY TENTERFIELD, DAVID WILLIAM CORNEY

|

In supplying the following story of the early days of Tenterfield as told to him by Mr. D. W. Corney, the secretary to the Tenterfield Historical Society, Mr. N. Crawford, writes:

Mr. Corney will celebrate his 85th. birthday tomorrow (Friday), October 2. Although of so mature an age he is still well and active and capable of doing a good days' work at his trade. In addition, he is billiards marker at the School of Arts each night, and on Saturday afternoons. "Bill" is a keen' bowler, and plays a remarkably good game. Last year at Stanthorpe he was the second oldest bowler in the "over 70" match. In his younger days, Mr. Corney was a keen cricketer, and scored the first century in Tenterfield, winning a bat presented by the late Mr. William Held. "Bill" scored IIS. In one season he won all trophies, but was presented with five only. "Bill" says they reckoned he had enough, so they gave the other one to Charlie Krahe. Mr. Crawford says Mr. Corney has just finished painting his house and is now painting the carshed, and looks like living to 200. Here is Mr. Corney's story: |

"My father, David English Corney, was a. native of England, being born, I think, in Gloucester in 1834. When a young man he emigrated to Australia, landing in Tasmania, where he resided for a while, then coming to Grafton, on the Clarence River, where he engaged in his trade of wheelwright, coachbuilding, shipwright, and builder.

MY MOTHER

While on the Clarence he met and married my mother, Miss Clarisse Matilda Wallis. She came to Australia in a companion ship to the ill-fated 'Dunbar.' They were warned against attempting, to enter Sydney Heads at night, but the captain of the 'Dunbar' took the risk, with the result that he mistook- The Gap for Sydney Heads in the darkness.

His ship drove into the rocky shore with the loss of all but one. The other ship entered safely in the morning. After a period in Sydney, my mother went to the Clarence, where she met mv father.

SETTLING IN TENTERFIELD

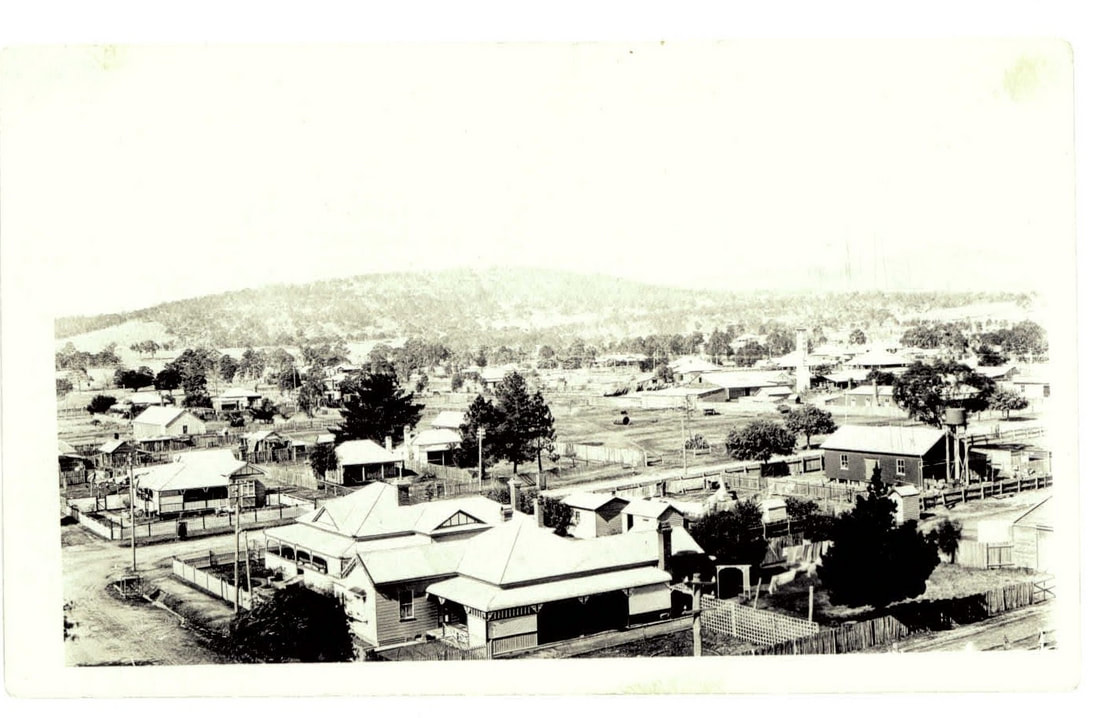

After their marriage, my parents came to Tenterfield in 1866, where my father worked at his trade. "Their first home was in Bulwer-street, what is now the remodeled home of the Hon family. There I was born on October 2, 1868. Later the home was further north in Bulwer Street, on the hill between Molesworth and Martin Streets.

BUILDINGS ERECTED

Amongst the buildings erected by father were: The Oddfellows' Hall, Town Hall (original part); the old brick houses below the Town Hall in Manners-street; Isaac Whereat' residence opposite 'Stannum, ' Isaac. Whereat's new residence, now the home of Mr. and Mrs. Terry Landers: Mrs. H. Kline's residence in the same local, extensive alterations to the original School of Arts buildings. Completion of the Post Office, when the contractors failed. My father was then foreman of works, under Thomas Lewis, storekeeper, who took over the completion of the contract.

DEPRESSION AND CHANGES

Eventually conditions became so bad, carpenters' wages being 5 shillings per day, that my father decided to open a coach-building business. This was situated - at the rear of the home in Bulwer street, Hon's present home. The business was later removed to a building in Highstreet. opposite the Royal Hotel. Many buggies, drays, carts, sulkies,

and other vehicles were built there. My father took an active interest in public life, and served as an Alderman in early Councils. In 1882 he served a term as Mayor.

His death took place on June 7, 1920, at the age of 86. My mother died on May 9, 1931, aged 91 years.

TENTERFIELD MY HOME

As I mentioned previously was born in Tenterfield on 2/10/1868. With the exception of a few years spent in North Queensland and Tasmania, my life has been spent in my home town. I was educated at Tenterfield Public School, the old wooden one, which was demolished when the present brick school was erected. My first teacher

was Paddy Walsh, who was a terror to the pupils. Other teachers were Messrs. Studdy, Pearson (brother-in-law of Mrs. H. Kline) and William Marshall, a keen cricketer. A few years ago, I heard that Mr. Marshall was living retired in Croydon in Sydney, and I visited him. He was delighted to see me, and we had a long chat, about old times and experiences.

Amongst fellow scholars were: Billy and Charlie Whereat, Edward's sons, Syd Whereat, Isaac's son, who died recently in North Queensland, Bob Peberdy, and Albert and George Young. There were large deep pools in the creek near the school, and we boys used to swim there.

AT WORK

On leaving school, I worked with my father at carpentering and other work. The first job was repairing the Public School and building an underground tank in the school ground. This was lined with brick. I assisted with the remodeling of the School of Arts and completing the Post Office. The foundation of the Post Office was a fine job, and there was never a crack or fault in it. The best, workmanship was also put into the. windows, doors and fittings, all of which were hand made. Another job I worked on was shingling the engine shed at the railway station, when the railway was built. The officer in charge of the work would not pay for it until it rained, to see if it would leak. The rain came, it did not leak, and we were paid.

A DARE-DEVIL BROTHER

My brother Charlie worked with us in completing the Post Office. He was fearless, and up to all kinds of pranks. When the tower of the Post Office had been completed, other than the railing and clock, Charlie stood on his I head on top of the tower. On another occasion he stood on his head on one of the high sides of the old Manners street bridge, the original one. Sgt. Hicks finally cautioned him against such-dangerous practices. Later, however, in Hughenden, North Queensland, where he went to live,

he secured an unmentionable item of crockery from an hotel bedroom climbing a tall tree in a main street, he tied it near the top, nearly 80 feet from the ground. There it remained, to the amusement of residents and passers-by, till blown down by a gale.

WORK IN HUGHENDEN

After some years work in Tenterfield, I spent two years in Hughenden. which was then the terminus of the railway running west from Townsville. My work was coachbuilding. The chief vehicles built were tabletop wagons to carry 20 tons. These were used for carriage of wool and goods across the great plains leading to the Gulf country and to Cloncurry and the far north-west of Queensland. Five hundred teams were then engaged in the traffic. When the rains came, all road traffic in goods was held up. Mud, floods and boggy tracks across the plain made roads untrafficable. Great floods took place in the nearly Flinders River, and in one of them two men were drowned while I was there.

Usually the bed of the river was a wide, sandy bed with the water running through the sand underneath. It was also very hot there, and rain was measured in feet, not inches.

TASMANIA, NEXT MOVE

My next move was from the extreme heat of. North Queensland to the cold climate of Hobart. On my arrival, there was snow on Mt, Wellington nearby, and I was nearly frozen. I was often up on Mt. Wellington during my two years stay. The flora and scenery were beautiful, and it was a great place for berries. Hobart secured its water supply from Fern Tree Bower at the foot of the mountain. I was engaged in coachbuilding while in Hobart. Being fond of sport, and cricket in particular I joined a team which played in the Domain. The leader of a rather exclusive club, Trinity Club, named Scholick, who had been watching me play one day, invited me to join their club. I did so, and had many enjoyable games in Hobart and along the Huon River and district. I won the bowling average that year.

RETURN TO TENTERFIELD

On returning to Tenterfield I worked for Louis Krahe at my trade. Later I worked for Pat. Hawkins, next to the Telegraph Hotel, for 18 years. My next work was for Frank j Schofield, whose shop was situated on the site of Jack Cooper's present home in High street. Later I bought the business. My next occupation was clerking for the New England Coy, who had the mail contract to the coast. There were big mails then, as the North Coast railway was not then completed. When the Fire Brigade was established in 1896 I was

appointed the first Captain. I held the position for 34 years and on retiring received a. long service medal with two bars. In recent years I have been mostly engaged in hood work for cars and similar work.

Chapter 1 INDECISION

“Today was the strangest of days. I set off from home on a mission but I became afeared and returned to the cottage. My dear friends won’t forgive me I am sure. Mama surprised me for she bade me complete my task though it will grieve her so.”

Matilda’s diary February 3rd, 1857

Matilda bid her mother goodbye, before shutting the door. She knew her ma wouldn’t hear her words, bent over the steaming copper, her coarse hands scrubbing away at the stained linen. Matilda’s goodbye today felt laced with sorrow, knowing the gravity a farewell would soon mean. Balancing the wicker basket of laundry onto her hip, she hitched her skirt and stepped down onto the street. Although it was cold and drizzling outside, Matilda was relieved to be out of the tiny cottage with its web of clothes lines heavy with wet washing, the walls dripping with condensation and the constant smell of damp.

She felt the thin soles of her shoes squelch and cursed the road that was either mud in winter or dust in summer. Matilda made her way down the narrow streets, skirting the children in their ragged clothes rolling a hoop back and forth and pressing herself into a doorway as a dray rounded the corner sending a spray of dirt up. ‘Blast you.’ she muttered looking down at her splattered apron. She was thankful that her ever practical Ma insisted on brown aprons for errands. Matilda lifted the cover on the laundry basket and was relieved to see the snowy white folds beneath were unmarked. 'I’d better hurry.’ She thought. ‘I don’t have long before Ma notices I’m away.’

She stepped quickly along the maze of tiny streets, greeting towns folk and dodging children and animals. On the edge of the town she crossed the field to reach the Manor, opening the gate into the manicured garden. If Matilda arrived late in the day to deliver her washing, the lamps would be lit and she could glimpse the front parlour as she passed by. Once she had dared to peek through the gleaming windows and saw a room of such lush beauty it took her breath away. The walls were lined with gold embossed swirly wallpaper hung with a collection of gilt edged paintings. There was a selection of soft comfortable chairs, little wooden tables and large green palms in bronze pots. A canary fluttered and sang in its pretty cage while glass domes held vibrantly coloured birds immobilised among a forest of foliage. The dark timber floor was strewn with thick rugs of a deep red. Sometimes Matilda lingered at the Manor lost in fantasies of a different life. She imagined herself in the chair by the window, wearing a fine garment full with petticoats, her hair coiled in plait loops sprinkled with pearls. She would wile away her days in luxury, servants tending her every need. Today though she walked quickly to the back door, handing the basket of laundry to the maid and collecting the calico sack of dirty washing, slinging it over her shoulder.

As she approached the Vestry she saw her friends gathered on the stone wall outside the church, excited and restless, their limbs in motion like four jittery foals. She watched them for a minute and felt a sudden pang of anxiety at the thought of their plan. ”Ah here she is.”, said Jane, smiling as Matilda made her way over. “Ready then?” “Umm, I’m not so sure now.” Matilda mumbled. “What? Tildy! No! It was your idea. You were the one who wanted this.” Jane cried.

The girls tumbled from the wall in shock and formed a semicircle around Matilda. It was true that she had first raised the idea of moving to the Colony. She had been summoned to her neighbour’s house to read a letter. In the dim circle of lamplight, the couple had sat hunched over the page, eager for Matilda to tell them what their son in Australia had to say. Jacob had fled Wiltshire with hundreds of other desperate souls six years before.

One of the lines stuck in Matilda’s minds, ‘We eat like Royalty here. Every night a joint of meat with all the trimmings. Milk for the children.’

The thought of a sumptuous meal like that to feast on instead of the meagre pickings on her own dinner table each night fired Matilda’s imagination. Then they’d seen the poster:

The Colony needs you. Single girls and women from country-villages! You are the sort required in New South Wales. It will be the happiest, perhaps the only happy incident in your lives. You will obtain service, high wages and husbands as soon as you please. Your passage paid for plus 12 pounds on arrival. JB Wilcox, Agent for the Commissioner will be in Broad Blunsdon August 20th and 21st, 1857. Apply at the Vestry.

“Things will be so much better Tildy.’ Emma said taking Matilda’s hand. ‘What is there for us here? Nothing but toil for no reward and marriage to one of the ninnyhammers here, endless bairns to feed.” Matilda sighed. “True, yes. But everything I know and love is here. My ma and da. My sister and brothers. My grandparents.” Matilda gestured to the river and hills behind them. “All of this. It’s our home.” “Pffff’ scoffed Jane. “Your da’s away all the time and when he’s home he’s at the alehouse with my da. Your ma works night and day, her hands red raw. Your grandparents are ailing.” Jane threw her arm out. “And this…this is nothing compared to money in our pockets, food in our bellies. Sea and sunshine. Freedom.” “Besides”, said Lizzie. “Mr Wilcox is only here for two days. This is our chance.” The girls linked arms and moved to the Vestry door. Jane lifted the brass knocker. The heavy wooden door creaked open and a servant peered out at them. “We’re here to see Mr Wilcox. For the passage to Australia.” Jane’s voice was firm. Matilda panicked, lifted her skirts and ran, the sack of washing pounding against her narrow shoulders. She could hear the chorus of voices beseeching “Tildy come back. C-o-m-e b-ac-k."

Tears streaming down her face, she rushed along the narrow streets, dodging obstacles, back to the safety of her home. “Ma. Ma.” She called as she burst through the cottage door. “Where are you ma?” She found her mother on a stool, hidden by the curtain of the sheets, a cup of warm tea in her hand. “Oh Ma. I love you so.” Matilda knelt at her feet, placing her head in her mother’s lap. Her mother stroked her daughter’s thick brown curls. “And I love you my darling girl.” Matilda closed her eyes, calmed by her mother’s attention. “But that is why I want more for you Tildy. A new life away from the torment that each day brings. This misery. This exhaustion. The constant worry like a shadow on each day.” Matilda snapped her head up, her mouth hung open. Her mother smiled and nodded slightly. “You are a clever girl Matilda and you have the chance of a new life. Take it. I beg you. Take it.” “Ma ….. how did you…?” Matilda was puzzled but her mother leant forward and pressed her fingers to Matilda’s lips as she rose from the stool. “Now we have work to do Matilda. Bring me that dirty washing.”

That night as the family hovered over their thin turnip soup Matilda watched them intently, drilling the memory of each one into her heart. Her lovely Lizzie with her fall of auburn hair over her small serious face, rascal George with his quick wit and mischievous ways, and little Charlie, the baby. Always happy and smiling safe in the bosom of his ma and siblings. Her grandparents too, bent and frail like two tiny twigs. She was glad her Da was away, working as a mason in Somerset and his surly presence wasn’t at the table tonight.

Chapter 2 The DECISION

“Today I took the first step and as a run away horse there shall be no stopping me. I told my friends that I am united with them now. If fate’s hand means we are to go to the Colony, we pray that we shall have the comfort of each other on the long journey.”

Matilda’s diary February 4th,1857

In the morning Matilda roused early from the pallet, covering her brother and sister with her own blanket and creeping past the sleeping bodies of her ma and Charlie, her grandparents huddled together like two little moles. She chuckled to herself at the chorus of snuffles, sighs and snorts that filled the room. Sleep was a blessed respite from the toil of the day. She washed her face in the bowl by the window, dressed quietly and left the cottage.

At the vestry the Parson and Mr Wilcox were eating their breakfast and the servant bade her wait in the dark wooded parlour. The clang of cutlery and slurping made her stomach clench. She knew her own breakfast would be a hunk of bread and cup of weak tea.

When she left the men an hour later, she clutched two certificates to complete; one attesting to her moral character and one to verify her physical and mental health. The outcome would be in God’s hands and Matilda determined that she would accept whatever happened and not torment herself with worry until then. Flushed and sweating she arrived back at the tiny cottage and the day’s toil that awaited her.

Two months later a letter arrived for Matilda. The envelope felt like a heavy weight in her hands, equal parts ominous and auspicious. She slipped it into her apron pocket to read later, her fingers worrying at the paper all through the day. In the quiet of the night, she crept to the kitchen, lit the stub of a candle and opened the letter: ‘Dear Mistress Wallis. Thank you for your application for assisted passage to Australia. We are pleased to advise you that, due to your moral character and good health, assisted passage is granted with the following conditions….’ Matilda put the letter down, her breath ragged, and sat very still. After a few moments she summoned her wits and read on:‘You are booked to travel on the Zemindar, leaving from London on May 30th, 1857, scheduled to arrive in Sydney, New South Wales on August 25th, 1857.’

Chapter 3 LEAVING HOME

“Everything is done now. Tomorrow we will walk away from all that we know and love. I will not look back for my heart is sure to break and I will be rooted to the spot and never leave.”

Matilda’s diary May 21st, 1857

Matilda could not sleep, her mind full of thoughts. She tossed and turned on her pallet, trying not to disturb her family’s sleeping bodies. She could hardly believe that within hours she would be leaving life as she knew it. Her few possessions stood ready in a calico bag waiting by the door and a small cloth packet of food for the journey. When the edges of the sky finally began to rim with light, Matilda roused and crept into the kitchen. Her mother was sitting at the table, a cup of tea and thick slice of bread in front of the chair next to her. Matilda sat down and her mother took her hand. No words passed between them, the enormity of the moment beyond words. Matilda finished her breakfast, kissed her mother’s wet face and, clutching her bag, left the house without looking back.

The girls had arranged to meet on the edge of the village at first daylight. Matilda was the first to arrive and was surprised to see a group of people already gathered there. One by one as her friends arrived, more people followed; families, neighbours and friends. Matilda was thrilled to see her own family hurrying towards them, her mother holding baby Charlie, her siblings rushing ahead and her beloved grandparents shuffling behind, doing their best to keep up. Nearly the whole village had turned out to bade them farewell. The atmosphere felt buoyant now, people chattering excitedly full of advice and well wishes. The girls finally managed to extricate them and set off on the path, beginning the climb up the green hill towards the next village. They looked back at the waving hands, the figures of their loved ones became smaller and smaller and the chorus of voices fading out until the girls reached the peak of the hill. They turned and gave a final vigorous wave before making their descent down the other side.

It seemed like a dream that they were truly on their way. They skipped along the narrow path towards Wootton Bassett where they stayed overnight with Matilda’s paternal grandparents in their tiny cottage, chattering into the night until Grandpa called out, “Shut it you lot.”, and they lay still but wide eyed until pale light trickled through the tiny window.

At the station, the platform was already crowded with passengers jostling to board the train. The friends had never travelled on anything other than a horse and dray and more often than not walked everywhere. Matilda wondered at it all; the big engine with its enormous steaming snout and massive wheels, the ladies and gentlemen in their fine dress and fancy hats, towers of luggage at their feet, children shifting from foot to foot eager to be on board, porters running up and down lugging trunks and portmanteaus onto the train. Standing to the side huddled a cluster of village folk and a collection of ragged children. Matilda recognised the fear in their pinched faces at travelling by train for the first time. She was comforted by the sight of the group, similar to the town people she’d left behind.

The girls were allocated to the last carriage whose centerpiece was an enormous cage which would hold a mountain of travelling trunks. Around the edges were a few wooden benches which filled up quickly leaving the girls to stand in the throng of people near the doors. As the train chugged out of the station, they began to share their stories, nervous about what lay ahead. Many were moving to London to try their luck at finding a job and the hope of a better future away from the grinding toil of subsistence living. A few among them were also bound for the Colony and Matilda’s racing heart quietened a little knowing that there were many like themselves, journeying across the oceans for far off shores, leaving the comfort of their families and villages behind.

It was stifling hot in the carriage and the smell of unwashed bodies was overpowering. Smoke and soot wafted in from the chugging engine. Matilda’s stomach heaved as the railway car rattled and swayed, lurching to a stop now and then to replenish the water for the boiler and the stack of wood for the fire. At times the journey was so slow Matilda quipped to her friends, ‘Even walking would be quicker than this’. At each station the passengers hurried onto the platform to gulp in the fresh air or take a deep drink from the water fountain and relieve themselves in the outhouse before the bellow of the horn summoned them back on board.

Chapter 4 LONDON

“There can be nothing more vile than this city and its filth and stench and deafening noises. The hovels and people in rags and dirty urchins. We are fortunate to be in the care of the Ladies but their good advice is wearying. We are counting the days till we set sail.”

Matilda’s diary May 27th, 1857

The fields and villages stretched on mile after mile, until abruptly they merged into a crowd of buildings, towering warehouses, makeshift houses, people moving quickly about their business. The train drew to a stop at Paddington station, London. The five friends looked in awe at the enormous glass dome overhead with its ornate iron curls and the lines of platforms and trains. Carried along with the crowd they nearly missed the woman and her sign. ‘Female Emigration Society.’ Introducing herself as Madam Wheeler, she commanded the girls to follow her up the stairs and onto the road.

As they came into the open a bank of hot air hit them and they lifted their aprons to cover their noses, assailed by a mix of unpleasant odours; acrid smoke, sewer, dung, urine and lime. Smog stripped the scene of colour leaving everything ash grey; buildings, horses, carts, people. Madam Wheeler seemed to pay no heed to any of it and gestured back to them to make haste. They hurried on but their heads swivelled this way and that, astonished at everything before them; the narrow streets strewn with refuse, dwellings crammed together haphazardly, men and women, dirty and ragged, children playing among the filth and rubbish. In the background the constant throb of noise; clacking of hooves, grinding of wheels, people yelling at each other in words they couldn’t decipher and beyond that that the clank and clatter of machinery.

Soon they arrived at Red Lion Square and Matilda was relieved when they turned into a quiet clean street leaving the chaos behind and Madam Wheeler bade them enter a simple, white washed, two story house. There were many other girls already settled in the home, also from villages like their own. Each day they were kept to a strict routine of ablutions, prayer and bible reading, chores, cooking and stitching their cloaks for the journey ahead. Matilda and her friends were thankful for the sanctuary and, used to hard work, they found the regime easy enough especially with their bellies full. There was much advice proffered by the ladies which soon became tiresome to the girls and they could not help but to grimace as yet another snippet was delivered.

‘

Avoid affectation; it is the sure test of a deceitful, vulgar mind. The best cure is to try to have those virtues which you would affect, and then they will appear naturally.’ You must carry your good manners everywhere with you. It is not a thing that can be laid aside and put on at pleasure and must be the effect of a Christian spirit running through all you do, or say, or think. ‘On board the ship, your conduct, your deportment and your dress must be impeccable.’ Do not indulge in extravagant notions and think you are to be fine ladies. Try and procure respectable service. A well conducted young woman will be much prized if she be a willing, active servant.’

From ‘The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness,’ by Florence Hartley

The day before the Zemindar ship was to leave the girls went on an outing to St Katherine’s Wharf to wave six of their house mates off on the Dunbar ship, bound for Sydney. The docks were a bustling, stinking, noisy place. Enormous ships with billowing sails crowded the river, little boats bobbed on the water’s edge and cavernous buildings rimmed the banks. Crowds of people jostled on the docks their voices competing with the clank and hum of machinery. A cloud of stench hung over everything; soot, salt and fish, damp wood, tobacco and sweat. The girls went to the Emigration Depot which thronged with people waiting for their turn to sail. The depot was a cavernous space, cold and dark, crowded with people hunched together on the benches, like sad ragged mounds. The floor was littered with straw and coats and capes, where they’d spent the night. Matilda was grateful that they’d been so well cared for by the ladies at the Female Emigration Society. As their friends crowded into the small boat to take them out to their waiting barque, the girls called to each other, “We’ll meet again in the Colony. Safe travels.” The next day Matilda, Emma, Jane, Lizzie and Mary were back on the dock, with their trunks well stocked for the journey ahead, courtesy of the fine women at the Female Emigration Society.

Chapter 5 BOUND FOR AUSTRALIA

“We have already come so far but today we will cross the ocean for 100 days. What might befall us on this long journey? Will we truly arrive in the Colony? God bless our journey and keep us safe.”

Matilda’s diary May 30th, 1857

Deep in the stern of the ship were the steerage quarters where the five friends would sleep and eat for the months ahead. The space was already crowded with women, the air warm with the press of bodies and stale with breath. The berths were narrow and close together, the height between each bunk so squashed there would be no sitting upright. A long trestle table and benches nailed to the floor, took up most of the space between the beds. Far at the back was a curtained water closet and a tiny kitchen off to the side. More women arrived down the stairs as Matilda looked on in dismay. At the final count there were sixty four single women crammed into the narrow space.

Matron Sloan, a big imposing figure commanded the women to attention in a booming voice, “As you are aware this will be a long journey. We will follow a strict routine from the time you are woken at am until bed at 8pm. I will not tolerate any idleness and you will be fully occupied at all times. You are not to converse with any male person, passenger or crew. Your conduct must be impeccable if you are to secure good positions in the Colony and you must be obedient to all of my orders. Your name is on your berth and that will be your bed for the entire journey. Please stow your belongings on your bed and then we will go through the Messes before we go upstairs to listen to Captain Jarvis and Surgeon Spencers’ address."

It wasn’t long before the roll of the ship on the waves brought on seasickness that kept the women confined, retching into buckets and groaning on their narrow beds. As the days passed, the passengers settled into a rhythm and largely managed the challenges of the cramped and difficult conditions. The heat at times was unbearable and fatigued everyone but the work had to be attended to. The chores were rigorous, keeping the berths clean, washing clothing, preparing meals, washing dishes, sweeping and scrubbing. There was prayer and bible reading and sometimes taking care of children from one of the families in the next section. Any spare time was spent on needlework which was given out regularly by Matron. Matron’s favourite refrain was “Cleanliness is next to godliness.” which she would repeat so many times it was like a chant.

Most of the girls were obedient and compliant but there was a small group who were obstinate and rebellious, causing trouble almost daily. There were constant quarrels and sometimes physical attacks, biting, scratching and kicking. They were abusive to the Matron with frequent name calling and threats of violence. At times they were so full of fury about some triviality, and caused a terrible din that went on hour after hour. Matron would try and divert the girls, leading them in singing or a game but many a time had to call on the Captain and the Surgeon to bring things to order again. Matilda kept her head down and tried to avoid the trouble makers.

The food was sustenance only; gruel for breakfast, biscuits and pease or salted meat for lunch and broth for dinner. On occasion there was suet and raisins. Matron insisted on a dose of sour lemon juice regularly to ward off scurvy but it was water that caused the most problems for the women. When the weather was hot their allocation was quickly drunk but as the days turned into weeks the water began to taste foul, the barrels contaminated with rotting vermin. The rebels made a racket, banging pots and screaming like banshees until eventually the water allocation was replenished. For once Matilda was grateful for their ferocity as it was unbearable to be parched without relief.

Matron insisted on regular exercise, forcing the girls to do laps around their quarters if they were battened down. When the weather was good, Matron didn’t need to encourage anyone to be on deck, even though there was much hard work to do. All the bedding was brought up to air, washing done and the floors scrubbed with vinegar and chloride of lime to keep disease at bay. Emboldened by the sense of freedom, the women stole coy glances at the muscular sailors attending to the ship tasks. The men in return blew them bawdy kisses and showed off their bulging biceps. These days on deck were sweet but when they rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean the seas became angry and the sky stormy for days on end. The hatch was fastened and it was dark and stuffy and vibrated with the terror of sixty four women crying out or beseeching God in prayer, convinced of catastrophe; the ship was on fire, the ship was tipping over, the mast and rigging were broken, the water was rushing in through the port holes. The stench of days of vomit and piss and shit was unbearably suffocating. Matilda was full of despair, convinced she and her friends would die here on this lonely ocean.

By the time the ship drew near Australia and the seas calmed down, six infants, one by one, had passed away from illness. Their tiny bodies were wrapped in canvas or nailed into a makeshift coffin, weighed down with lead and hoisted overboard, forever lost to the bottom of the vast, cruel ocean. Matilda watched in horror as a mother hurled herself at the railing, desperate to join her child, her face contorted in agony, a terrible keening pouring from her mouth. The grief of the mothers filled the ship with sadness.

It was a happy event when one of their companions, Fanny, was delivered of a bonny baby boy. No-one knew she had been pregnant. A tiny woman, her growing form was well hidden by the cloak she wore. The women had thought her demeanour strange and wondered at her layers of clothing when the rest of them were stripped down to their petticoats in the heat. Matron rushed to her side when she panted, “Help me please.” and quickly realising she was in labour scuttled off to get the Surgeon.

A woman, Susan, called out to her retreating figure, “Wait. Stop.” Matron turned on the stair quizzically. “My mother is a midwife and I have attended many births with her. I think I can deliver this baby.” Matron hesitated. “Get hot water and cloths. Scissors.” Susan commanded bringing Matron to heel.

Several girls hurried off to collect what was needed. It was a long labour but blessedly uncomplicated and baby Samuel was delivered skilfully and without incident. A river of happiness spread through the quarters. There was a baby in their midst. Matron, although disgusted at a bastard child, could not refute the change in the mood that Samuel brought and was relieved to have some respite from the bedlam.

Chapter 6 the ARRIVAL

“We are but moments from our destination and soon will be on steady ground. We don’t know what awaits us but think that we are likely to be separated. We are sworn to make every effort to be connected for we are as sisters.”

Matilda’s diary August 25th, 1857

Mercifully the wind and rain stilled and the sun warmed the vessel on the final week of the journey. Now that the women were so close to their destination the group was subdued, each woman lost in her own thoughts; grief or relief at what was left behind, the tumultuous events of the journey, trepidation and excitement at what lay ahead.

By the time the Zemindar approached South Head, the deck was bursting with passengers excited now not to miss the first view of Sydney Cove. The women, though thin and exhausted, had dressed in their best outfits for the last stage of the journey. It had been a long and difficult three months but now the sun was pouring down, land was in sight and the exhilaration of the passengers was infectious. Standing on the warmth of the deck under the blue sky, the hell of steerage felt far away. Matilda raised her face to the sun’s rays and enjoyed the salty breeze that blew over her body.

Suddenly Matilda became aware of a commotion. She peered anxiously over the heads in front of her and glimpsed the sea of debris between the shore and the boat. It was a floating mess of chaos, the paraphernalia of lives strewn carelessly in the water.; bundles of rags, wooden palings, a shoe, a barrel.

A man at the front cried out ‘They are not rags, but bodies.’ A silence spread over the crowded deck, the horror too great for words. Someone moaned, “What terror has befallen these poor ones?”

Captain Jarvis appeared and ordered everyone back to their quarters. He looked rattled, his face tense and his voice shaky. He knew the wreckage belonged to the Dunbar and the Captain, James Green, was his dear friend. Nervous and fearful, the group of passengers quickly thinned out returning to their cabins and their dark steerage prison. The women sat hunched on their narrow beds, staring into space. 'What had happened to the ship now in pieces?’ No one dared speak the question in every one’s minds, 'Will we suffer the same fate?’

After a long wait, everyone was released to gather once more on the deck as the ship moved towards Circular Quay. It was a somber mood, each person acutely aware of their own good fortune when the ship before them was smashed and splintered against the rocks, all its passengers dead.

Before disembarkation, Captain Jarvis led the crowd in prayer. Matilda and her friends held hands tightly, their heads bent in reverence. “Dear Lord, we are grateful for our safe journey and that you have not called us to your side at this time. We pray for all the poor souls from the Dunbar and are heartened that they are now in your loving care.”

Matilda let out a guttural cry like an animal in pain and she and her friends fell against each other, sobbing at the realisation that it was their dear companions from the Female Emigration Society now among the dead floating in the water. The prayer ended and people began peeling away and moving towards the hold. The friends steadied themselves and joined the throng of people readying to leave the ship. Small boats were lining up to transport the passengers to the shore.

The scene before them was full of beauty and promise, like a landscape painting. The sun shone overhead. The sky glowed cerulean blue, dotted with cotton ball clouds. Beneath them the sparkling sea was strewn with bobbing boats. The scalloped coastline around was lush and green and ahead, the fine buildings of Sydney city stretched into the distance. Matilda stood for a moment quietly taking it all in. Then she took a big breath and stepped into the waiting boat and into her future.

Chapter 1 INDECISION

“Today was the strangest of days. I set off from home on a mission but I became afeared and returned to the cottage. My dear friends won’t forgive me I am sure. Mama surprised me for she bade me complete my task though it will grieve her so.”

Matilda’s diary February 3rd, 1857

Matilda bid her mother goodbye, before shutting the door. She knew her ma wouldn’t hear her words, bent over the steaming copper, her coarse hands scrubbing away at the stained linen. Matilda’s goodbye today felt laced with sorrow, knowing the gravity a farewell would soon mean. Balancing the wicker basket of laundry onto her hip, she hitched her skirt and stepped down onto the street. Although it was cold and drizzling outside, Matilda was relieved to be out of the tiny cottage with its web of clothes lines heavy with wet washing, the walls dripping with condensation and the constant smell of damp.

She felt the thin soles of her shoes squelch and cursed the road that was either mud in winter or dust in summer. Matilda made her way down the narrow streets, skirting the children in their ragged clothes rolling a hoop back and forth and pressing herself into a doorway as a dray rounded the corner sending a spray of dirt up. ‘Blast you.’ she muttered looking down at her splattered apron. She was thankful that her ever practical Ma insisted on brown aprons for errands. Matilda lifted the cover on the laundry basket and was relieved to see the snowy white folds beneath were unmarked. 'I’d better hurry.’ She thought. ‘I don’t have long before Ma notices I’m away.’

She stepped quickly along the maze of tiny streets, greeting towns folk and dodging children and animals. On the edge of the town she crossed the field to reach the Manor, opening the gate into the manicured garden. If Matilda arrived late in the day to deliver her washing, the lamps would be lit and she could glimpse the front parlour as she passed by. Once she had dared to peek through the gleaming windows and saw a room of such lush beauty it took her breath away. The walls were lined with gold embossed swirly wallpaper hung with a collection of gilt edged paintings. There was a selection of soft comfortable chairs, little wooden tables and large green palms in bronze pots. A canary fluttered and sang in its pretty cage while glass domes held vibrantly coloured birds immobilised among a forest of foliage. The dark timber floor was strewn with thick rugs of a deep red. Sometimes Matilda lingered at the Manor lost in fantasies of a different life. She imagined herself in the chair by the window, wearing a fine garment full with petticoats, her hair coiled in plait loops sprinkled with pearls. She would wile away her days in luxury, servants tending her every need. Today though she walked quickly to the back door, handing the basket of laundry to the maid and collecting the calico sack of dirty washing, slinging it over her shoulder.

As she approached the Vestry she saw her friends gathered on the stone wall outside the church, excited and restless, their limbs in motion like four jittery foals. She watched them for a minute and felt a sudden pang of anxiety at the thought of their plan. ”Ah here she is.”, said Jane, smiling as Matilda made her way over. “Ready then?” “Umm, I’m not so sure now.” Matilda mumbled. “What? Tildy! No! It was your idea. You were the one who wanted this.” Jane cried.

The girls tumbled from the wall in shock and formed a semicircle around Matilda. It was true that she had first raised the idea of moving to the Colony. She had been summoned to her neighbour’s house to read a letter. In the dim circle of lamplight, the couple had sat hunched over the page, eager for Matilda to tell them what their son in Australia had to say. Jacob had fled Wiltshire with hundreds of other desperate souls six years before.

One of the lines stuck in Matilda’s minds, ‘We eat like Royalty here. Every night a joint of meat with all the trimmings. Milk for the children.’

The thought of a sumptuous meal like that to feast on instead of the meagre pickings on her own dinner table each night fired Matilda’s imagination. Then they’d seen the poster:

The Colony needs you. Single girls and women from country-villages! You are the sort required in New South Wales. It will be the happiest, perhaps the only happy incident in your lives. You will obtain service, high wages and husbands as soon as you please. Your passage paid for plus 12 pounds on arrival. JB Wilcox, Agent for the Commissioner will be in Broad Blunsdon August 20th and 21st, 1857. Apply at the Vestry.

“Things will be so much better Tildy.’ Emma said taking Matilda’s hand. ‘What is there for us here? Nothing but toil for no reward and marriage to one of the ninnyhammers here, endless bairns to feed.” Matilda sighed. “True, yes. But everything I know and love is here. My ma and da. My sister and brothers. My grandparents.” Matilda gestured to the river and hills behind them. “All of this. It’s our home.” “Pffff’ scoffed Jane. “Your da’s away all the time and when he’s home he’s at the alehouse with my da. Your ma works night and day, her hands red raw. Your grandparents are ailing.” Jane threw her arm out. “And this…this is nothing compared to money in our pockets, food in our bellies. Sea and sunshine. Freedom.” “Besides”, said Lizzie. “Mr Wilcox is only here for two days. This is our chance.” The girls linked arms and moved to the Vestry door. Jane lifted the brass knocker. The heavy wooden door creaked open and a servant peered out at them. “We’re here to see Mr Wilcox. For the passage to Australia.” Jane’s voice was firm. Matilda panicked, lifted her skirts and ran, the sack of washing pounding against her narrow shoulders. She could hear the chorus of voices beseeching “Tildy come back. C-o-m-e b-ac-k."

Tears streaming down her face, she rushed along the narrow streets, dodging obstacles, back to the safety of her home. “Ma. Ma.” She called as she burst through the cottage door. “Where are you ma?” She found her mother on a stool, hidden by the curtain of the sheets, a cup of warm tea in her hand. “Oh Ma. I love you so.” Matilda knelt at her feet, placing her head in her mother’s lap. Her mother stroked her daughter’s thick brown curls. “And I love you my darling girl.” Matilda closed her eyes, calmed by her mother’s attention. “But that is why I want more for you Tildy. A new life away from the torment that each day brings. This misery. This exhaustion. The constant worry like a shadow on each day.” Matilda snapped her head up, her mouth hung open. Her mother smiled and nodded slightly. “You are a clever girl Matilda and you have the chance of a new life. Take it. I beg you. Take it.” “Ma ….. how did you…?” Matilda was puzzled but her mother leant forward and pressed her fingers to Matilda’s lips as she rose from the stool. “Now we have work to do Matilda. Bring me that dirty washing.”

That night as the family hovered over their thin turnip soup Matilda watched them intently, drilling the memory of each one into her heart. Her lovely Lizzie with her fall of auburn hair over her small serious face, rascal George with his quick wit and mischievous ways, and little Charlie, the baby. Always happy and smiling safe in the bosom of his ma and siblings. Her grandparents too, bent and frail like two tiny twigs. She was glad her Da was away, working as a mason in Somerset and his surly presence wasn’t at the table tonight.

Chapter 2 The DECISION

“Today I took the first step and as a run away horse there shall be no stopping me. I told my friends that I am united with them now. If fate’s hand means we are to go to the Colony, we pray that we shall have the comfort of each other on the long journey.”

Matilda’s diary February 4th,1857

In the morning Matilda roused early from the pallet, covering her brother and sister with her own blanket and creeping past the sleeping bodies of her ma and Charlie, her grandparents huddled together like two little moles. She chuckled to herself at the chorus of snuffles, sighs and snorts that filled the room. Sleep was a blessed respite from the toil of the day. She washed her face in the bowl by the window, dressed quietly and left the cottage.

At the vestry the Parson and Mr Wilcox were eating their breakfast and the servant bade her wait in the dark wooded parlour. The clang of cutlery and slurping made her stomach clench. She knew her own breakfast would be a hunk of bread and cup of weak tea.

When she left the men an hour later, she clutched two certificates to complete; one attesting to her moral character and one to verify her physical and mental health. The outcome would be in God’s hands and Matilda determined that she would accept whatever happened and not torment herself with worry until then. Flushed and sweating she arrived back at the tiny cottage and the day’s toil that awaited her.

Two months later a letter arrived for Matilda. The envelope felt like a heavy weight in her hands, equal parts ominous and auspicious. She slipped it into her apron pocket to read later, her fingers worrying at the paper all through the day. In the quiet of the night, she crept to the kitchen, lit the stub of a candle and opened the letter: ‘Dear Mistress Wallis. Thank you for your application for assisted passage to Australia. We are pleased to advise you that, due to your moral character and good health, assisted passage is granted with the following conditions….’ Matilda put the letter down, her breath ragged, and sat very still. After a few moments she summoned her wits and read on:‘You are booked to travel on the Zemindar, leaving from London on May 30th, 1857, scheduled to arrive in Sydney, New South Wales on August 25th, 1857.’

Chapter 3 LEAVING HOME

“Everything is done now. Tomorrow we will walk away from all that we know and love. I will not look back for my heart is sure to break and I will be rooted to the spot and never leave.”

Matilda’s diary May 21st, 1857

Matilda could not sleep, her mind full of thoughts. She tossed and turned on her pallet, trying not to disturb her family’s sleeping bodies. She could hardly believe that within hours she would be leaving life as she knew it. Her few possessions stood ready in a calico bag waiting by the door and a small cloth packet of food for the journey. When the edges of the sky finally began to rim with light, Matilda roused and crept into the kitchen. Her mother was sitting at the table, a cup of tea and thick slice of bread in front of the chair next to her. Matilda sat down and her mother took her hand. No words passed between them, the enormity of the moment beyond words. Matilda finished her breakfast, kissed her mother’s wet face and, clutching her bag, left the house without looking back.

The girls had arranged to meet on the edge of the village at first daylight. Matilda was the first to arrive and was surprised to see a group of people already gathered there. One by one as her friends arrived, more people followed; families, neighbours and friends. Matilda was thrilled to see her own family hurrying towards them, her mother holding baby Charlie, her siblings rushing ahead and her beloved grandparents shuffling behind, doing their best to keep up. Nearly the whole village had turned out to bade them farewell. The atmosphere felt buoyant now, people chattering excitedly full of advice and well wishes. The girls finally managed to extricate them and set off on the path, beginning the climb up the green hill towards the next village. They looked back at the waving hands, the figures of their loved ones became smaller and smaller and the chorus of voices fading out until the girls reached the peak of the hill. They turned and gave a final vigorous wave before making their descent down the other side.

It seemed like a dream that they were truly on their way. They skipped along the narrow path towards Wootton Bassett where they stayed overnight with Matilda’s paternal grandparents in their tiny cottage, chattering into the night until Grandpa called out, “Shut it you lot.”, and they lay still but wide eyed until pale light trickled through the tiny window.

At the station, the platform was already crowded with passengers jostling to board the train. The friends had never travelled on anything other than a horse and dray and more often than not walked everywhere. Matilda wondered at it all; the big engine with its enormous steaming snout and massive wheels, the ladies and gentlemen in their fine dress and fancy hats, towers of luggage at their feet, children shifting from foot to foot eager to be on board, porters running up and down lugging trunks and portmanteaus onto the train. Standing to the side huddled a cluster of village folk and a collection of ragged children. Matilda recognised the fear in their pinched faces at travelling by train for the first time. She was comforted by the sight of the group, similar to the town people she’d left behind.

The girls were allocated to the last carriage whose centerpiece was an enormous cage which would hold a mountain of travelling trunks. Around the edges were a few wooden benches which filled up quickly leaving the girls to stand in the throng of people near the doors. As the train chugged out of the station, they began to share their stories, nervous about what lay ahead. Many were moving to London to try their luck at finding a job and the hope of a better future away from the grinding toil of subsistence living. A few among them were also bound for the Colony and Matilda’s racing heart quietened a little knowing that there were many like themselves, journeying across the oceans for far off shores, leaving the comfort of their families and villages behind.

It was stifling hot in the carriage and the smell of unwashed bodies was overpowering. Smoke and soot wafted in from the chugging engine. Matilda’s stomach heaved as the railway car rattled and swayed, lurching to a stop now and then to replenish the water for the boiler and the stack of wood for the fire. At times the journey was so slow Matilda quipped to her friends, ‘Even walking would be quicker than this’. At each station the passengers hurried onto the platform to gulp in the fresh air or take a deep drink from the water fountain and relieve themselves in the outhouse before the bellow of the horn summoned them back on board.

Chapter 4 LONDON

“There can be nothing more vile than this city and its filth and stench and deafening noises. The hovels and people in rags and dirty urchins. We are fortunate to be in the care of the Ladies but their good advice is wearying. We are counting the days till we set sail.”

Matilda’s diary May 27th, 1857

The fields and villages stretched on mile after mile, until abruptly they merged into a crowd of buildings, towering warehouses, makeshift houses, people moving quickly about their business. The train drew to a stop at Paddington station, London. The five friends looked in awe at the enormous glass dome overhead with its ornate iron curls and the lines of platforms and trains. Carried along with the crowd they nearly missed the woman and her sign. ‘Female Emigration Society.’ Introducing herself as Madam Wheeler, she commanded the girls to follow her up the stairs and onto the road.

As they came into the open a bank of hot air hit them and they lifted their aprons to cover their noses, assailed by a mix of unpleasant odours; acrid smoke, sewer, dung, urine and lime. Smog stripped the scene of colour leaving everything ash grey; buildings, horses, carts, people. Madam Wheeler seemed to pay no heed to any of it and gestured back to them to make haste. They hurried on but their heads swivelled this way and that, astonished at everything before them; the narrow streets strewn with refuse, dwellings crammed together haphazardly, men and women, dirty and ragged, children playing among the filth and rubbish. In the background the constant throb of noise; clacking of hooves, grinding of wheels, people yelling at each other in words they couldn’t decipher and beyond that that the clank and clatter of machinery.

Soon they arrived at Red Lion Square and Matilda was relieved when they turned into a quiet clean street leaving the chaos behind and Madam Wheeler bade them enter a simple, white washed, two story house. There were many other girls already settled in the home, also from villages like their own. Each day they were kept to a strict routine of ablutions, prayer and bible reading, chores, cooking and stitching their cloaks for the journey ahead. Matilda and her friends were thankful for the sanctuary and, used to hard work, they found the regime easy enough especially with their bellies full. There was much advice proffered by the ladies which soon became tiresome to the girls and they could not help but to grimace as yet another snippet was delivered.

‘

Avoid affectation; it is the sure test of a deceitful, vulgar mind. The best cure is to try to have those virtues which you would affect, and then they will appear naturally.’ You must carry your good manners everywhere with you. It is not a thing that can be laid aside and put on at pleasure and must be the effect of a Christian spirit running through all you do, or say, or think. ‘On board the ship, your conduct, your deportment and your dress must be impeccable.’ Do not indulge in extravagant notions and think you are to be fine ladies. Try and procure respectable service. A well conducted young woman will be much prized if she be a willing, active servant.’

From ‘The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness,’ by Florence Hartley

The day before the Zemindar ship was to leave the girls went on an outing to St Katherine’s Wharf to wave six of their house mates off on the Dunbar ship, bound for Sydney. The docks were a bustling, stinking, noisy place. Enormous ships with billowing sails crowded the river, little boats bobbed on the water’s edge and cavernous buildings rimmed the banks. Crowds of people jostled on the docks their voices competing with the clank and hum of machinery. A cloud of stench hung over everything; soot, salt and fish, damp wood, tobacco and sweat. The girls went to the Emigration Depot which thronged with people waiting for their turn to sail. The depot was a cavernous space, cold and dark, crowded with people hunched together on the benches, like sad ragged mounds. The floor was littered with straw and coats and capes, where they’d spent the night. Matilda was grateful that they’d been so well cared for by the ladies at the Female Emigration Society. As their friends crowded into the small boat to take them out to their waiting barque, the girls called to each other, “We’ll meet again in the Colony. Safe travels.” The next day Matilda, Emma, Jane, Lizzie and Mary were back on the dock, with their trunks well stocked for the journey ahead, courtesy of the fine women at the Female Emigration Society.

Chapter 5 BOUND FOR AUSTRALIA

“We have already come so far but today we will cross the ocean for 100 days. What might befall us on this long journey? Will we truly arrive in the Colony? God bless our journey and keep us safe.”

Matilda’s diary May 30th, 1857

Deep in the stern of the ship were the steerage quarters where the five friends would sleep and eat for the months ahead. The space was already crowded with women, the air warm with the press of bodies and stale with breath. The berths were narrow and close together, the height between each bunk so squashed there would be no sitting upright. A long trestle table and benches nailed to the floor, took up most of the space between the beds. Far at the back was a curtained water closet and a tiny kitchen off to the side. More women arrived down the stairs as Matilda looked on in dismay. At the final count there were sixty four single women crammed into the narrow space.

Matron Sloan, a big imposing figure commanded the women to attention in a booming voice, “As you are aware this will be a long journey. We will follow a strict routine from the time you are woken at am until bed at 8pm. I will not tolerate any idleness and you will be fully occupied at all times. You are not to converse with any male person, passenger or crew. Your conduct must be impeccable if you are to secure good positions in the Colony and you must be obedient to all of my orders. Your name is on your berth and that will be your bed for the entire journey. Please stow your belongings on your bed and then we will go through the Messes before we go upstairs to listen to Captain Jarvis and Surgeon Spencers’ address."

It wasn’t long before the roll of the ship on the waves brought on seasickness that kept the women confined, retching into buckets and groaning on their narrow beds. As the days passed, the passengers settled into a rhythm and largely managed the challenges of the cramped and difficult conditions. The heat at times was unbearable and fatigued everyone but the work had to be attended to. The chores were rigorous, keeping the berths clean, washing clothing, preparing meals, washing dishes, sweeping and scrubbing. There was prayer and bible reading and sometimes taking care of children from one of the families in the next section. Any spare time was spent on needlework which was given out regularly by Matron. Matron’s favourite refrain was “Cleanliness is next to godliness.” which she would repeat so many times it was like a chant.

Most of the girls were obedient and compliant but there was a small group who were obstinate and rebellious, causing trouble almost daily. There were constant quarrels and sometimes physical attacks, biting, scratching and kicking. They were abusive to the Matron with frequent name calling and threats of violence. At times they were so full of fury about some triviality, and caused a terrible din that went on hour after hour. Matron would try and divert the girls, leading them in singing or a game but many a time had to call on the Captain and the Surgeon to bring things to order again. Matilda kept her head down and tried to avoid the trouble makers.

The food was sustenance only; gruel for breakfast, biscuits and pease or salted meat for lunch and broth for dinner. On occasion there was suet and raisins. Matron insisted on a dose of sour lemon juice regularly to ward off scurvy but it was water that caused the most problems for the women. When the weather was hot their allocation was quickly drunk but as the days turned into weeks the water began to taste foul, the barrels contaminated with rotting vermin. The rebels made a racket, banging pots and screaming like banshees until eventually the water allocation was replenished. For once Matilda was grateful for their ferocity as it was unbearable to be parched without relief.

Matron insisted on regular exercise, forcing the girls to do laps around their quarters if they were battened down. When the weather was good, Matron didn’t need to encourage anyone to be on deck, even though there was much hard work to do. All the bedding was brought up to air, washing done and the floors scrubbed with vinegar and chloride of lime to keep disease at bay. Emboldened by the sense of freedom, the women stole coy glances at the muscular sailors attending to the ship tasks. The men in return blew them bawdy kisses and showed off their bulging biceps. These days on deck were sweet but when they rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean the seas became angry and the sky stormy for days on end. The hatch was fastened and it was dark and stuffy and vibrated with the terror of sixty four women crying out or beseeching God in prayer, convinced of catastrophe; the ship was on fire, the ship was tipping over, the mast and rigging were broken, the water was rushing in through the port holes. The stench of days of vomit and piss and shit was unbearably suffocating. Matilda was full of despair, convinced she and her friends would die here on this lonely ocean.

By the time the ship drew near Australia and the seas calmed down, six infants, one by one, had passed away from illness. Their tiny bodies were wrapped in canvas or nailed into a makeshift coffin, weighed down with lead and hoisted overboard, forever lost to the bottom of the vast, cruel ocean. Matilda watched in horror as a mother hurled herself at the railing, desperate to join her child, her face contorted in agony, a terrible keening pouring from her mouth. The grief of the mothers filled the ship with sadness.

It was a happy event when one of their companions, Fanny, was delivered of a bonny baby boy. No-one knew she had been pregnant. A tiny woman, her growing form was well hidden by the cloak she wore. The women had thought her demeanour strange and wondered at her layers of clothing when the rest of them were stripped down to their petticoats in the heat. Matron rushed to her side when she panted, “Help me please.” and quickly realising she was in labour scuttled off to get the Surgeon.

A woman, Susan, called out to her retreating figure, “Wait. Stop.” Matron turned on the stair quizzically. “My mother is a midwife and I have attended many births with her. I think I can deliver this baby.” Matron hesitated. “Get hot water and cloths. Scissors.” Susan commanded bringing Matron to heel.

Several girls hurried off to collect what was needed. It was a long labour but blessedly uncomplicated and baby Samuel was delivered skilfully and without incident. A river of happiness spread through the quarters. There was a baby in their midst. Matron, although disgusted at a bastard child, could not refute the change in the mood that Samuel brought and was relieved to have some respite from the bedlam.

Chapter 6 the ARRIVAL

“We are but moments from our destination and soon will be on steady ground. We don’t know what awaits us but think that we are likely to be separated. We are sworn to make every effort to be connected for we are as sisters.”

Matilda’s diary August 25th, 1857

Mercifully the wind and rain stilled and the sun warmed the vessel on the final week of the journey. Now that the women were so close to their destination the group was subdued, each woman lost in her own thoughts; grief or relief at what was left behind, the tumultuous events of the journey, trepidation and excitement at what lay ahead.

By the time the Zemindar approached South Head, the deck was bursting with passengers excited now not to miss the first view of Sydney Cove. The women, though thin and exhausted, had dressed in their best outfits for the last stage of the journey. It had been a long and difficult three months but now the sun was pouring down, land was in sight and the exhilaration of the passengers was infectious. Standing on the warmth of the deck under the blue sky, the hell of steerage felt far away. Matilda raised her face to the sun’s rays and enjoyed the salty breeze that blew over her body.

Suddenly Matilda became aware of a commotion. She peered anxiously over the heads in front of her and glimpsed the sea of debris between the shore and the boat. It was a floating mess of chaos, the paraphernalia of lives strewn carelessly in the water.; bundles of rags, wooden palings, a shoe, a barrel.

A man at the front cried out ‘They are not rags, but bodies.’ A silence spread over the crowded deck, the horror too great for words. Someone moaned, “What terror has befallen these poor ones?”

Captain Jarvis appeared and ordered everyone back to their quarters. He looked rattled, his face tense and his voice shaky. He knew the wreckage belonged to the Dunbar and the Captain, James Green, was his dear friend. Nervous and fearful, the group of passengers quickly thinned out returning to their cabins and their dark steerage prison. The women sat hunched on their narrow beds, staring into space. 'What had happened to the ship now in pieces?’ No one dared speak the question in every one’s minds, 'Will we suffer the same fate?’

After a long wait, everyone was released to gather once more on the deck as the ship moved towards Circular Quay. It was a somber mood, each person acutely aware of their own good fortune when the ship before them was smashed and splintered against the rocks, all its passengers dead.

Before disembarkation, Captain Jarvis led the crowd in prayer. Matilda and her friends held hands tightly, their heads bent in reverence. “Dear Lord, we are grateful for our safe journey and that you have not called us to your side at this time. We pray for all the poor souls from the Dunbar and are heartened that they are now in your loving care.”

Matilda let out a guttural cry like an animal in pain and she and her friends fell against each other, sobbing at the realisation that it was their dear companions from the Female Emigration Society now among the dead floating in the water. The prayer ended and people began peeling away and moving towards the hold. The friends steadied themselves and joined the throng of people readying to leave the ship. Small boats were lining up to transport the passengers to the shore.

The scene before them was full of beauty and promise, like a landscape painting. The sun shone overhead. The sky glowed cerulean blue, dotted with cotton ball clouds. Beneath them the sparkling sea was strewn with bobbing boats. The scalloped coastline around was lush and green and ahead, the fine buildings of Sydney city stretched into the distance. Matilda stood for a moment quietly taking it all in. Then she took a big breath and stepped into the waiting boat and into her future.